The Roman domus, or house, was not something that your everyday Roman could live in. Only some of the richest or most elite Romans could live in a domus, as most poorer Romans lived in apartment complexes known as insulae, which were cramped, dark, and very unsanitary.

Originally, most of these domus were only one story tall. However, the price of land soon shot upwards, forcing many Romans to start building upwards instead of outwards. As the height of buildings gradually rose, Augustus, the first emperor to do so, restricted the height of these buildings to 70 feet in order to prevent the dangers of having such high buildings. Soon after, Nero decreased the maximum height again, lowering it to 60 feet.

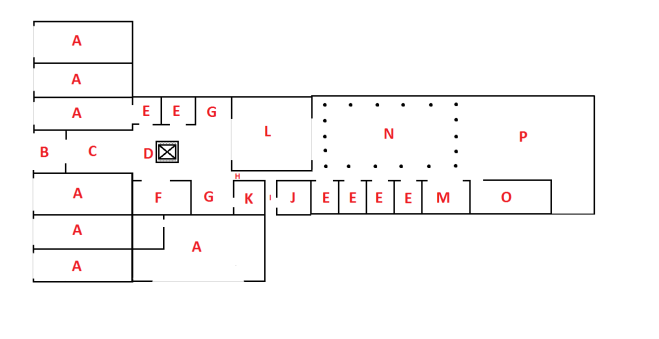

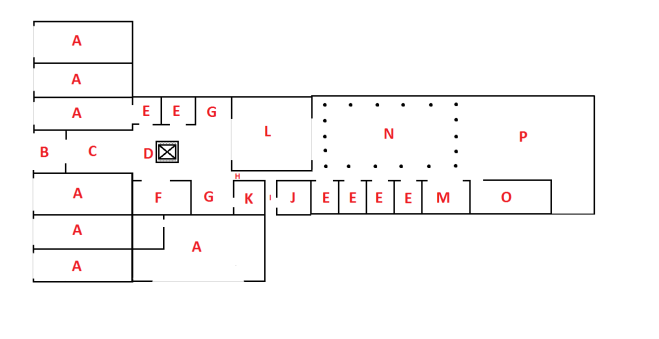

Now, less about all of this random stuff, let’s get into what some of the rooms in your typical Roman home could’ve been! Below is a drawing I’ve made of what a possible Roman domus could’ve looked like- the home of Ovum!

As you can see, there were quite a few rooms in your typical home, and some houses had even more than this! However, here are some of the more common things you could expect to see in your average Roman home.

A. These little things off to the side of Ovum’s fabulous house are shops! These could’ve been rented out to various other Romans, or Ovum could’ve managed them himself with his family! For example, you might see a baker (pistor), a banker, (argentarii), a barber (tonsor), or any one of the other types of jobs working here!

B. This is the vestibulum, a space between the door (which is called the janua or ostia) and the outside road (to the left of the drawing). The vestibulum, as shown in the drawing, is often surrounded only by 3 sides of the house, with the fourth side, of course, exposed to the outside road. Oftentimes, this was where things such as “Nihil intret mali” or “Cave canem” would be located on a mosaic (which mean “May no evil enter”, and “Beware of dog”, respectively).

C. This is also called the ostium, identical in name to the doorway of the house (many definitions of ostia often include both the doorway and the inner hallway in it)! Oftentimes, there would be a small room attached to the side of the ostium (not shown in the diagram) where a doorman (janitor or ianitor) and a dog would be kept. Those who didn’t cave canem would have a nice surprise on the other side of the front door!

D. Welcome to the atrium, or the main area of the home! Oftentimes, the atrium was used by the male head of household (paterfamilias) for receiving clients (cliens), handling business, and in general, just being the public area of the home! Here, we can see the impluvium in the center of it, which is a shallow pool for the collection of water. This pool water could be used for many purposes, including drinking and washing! How does the water get into the impluvium, you may ask? Well, the compluvium is the answer to that question! The compluvium, similarly located in the atrium, is a hole/skylight in the roof of the home that lets both sunlight, air, and water in. In fact, the compluvium oftentimes would be the only source of light for not just the atrium, but the surrounding rooms as well, as windows (fenestrae) were uncommon. Also located in the atrium would be various spinning devices for the women, and the lararium, a shrine to the lares, the household gods.

Interestingly enough, there were also many types of atria.

- The Tuscanium, or Tuscan, was an atrium that had no columns. Instead, it was supported by four perpendicular beams.

- The Tetrastylum was similar to the Tuscan, however, it had 4 columns supporting the four pillars, placed at the four corners of the impluvium.

- The Corinthium was also similar to the Tuscanium and the Tetrastylum. However, instead of just 4 pillars supporting the beams, there were more.

- The Displuvatium had it’s roof slanted in a way that the water fell outside the home instead of in the impluvium.

- The Testudinatum had no compluvium at all! It was roofed all over!

E. This is the cubicula, or bedroom! These were often very small, with separate cubicula for nighttime sleeping and daytime sleeping (cubicula nocturna and diurna). Those used for the former were known specifically as dormitoria. Oftentimes, these were also used as private meeting spaces, with more intimate guests being received and greeted here.

F. Similarly to ancient Greece, hospitality played a major role in the daily life of the Romans, both in public (hospitium publicum) and in private (hospitium privatum). When a guest arrived, they were oftentimes treated just as highly, if not higher, than even members of the family. Thus, many houses had special rooms for the reception and lodging of guests, known as hospitium. However, when houses did not have the hospitium, guests were often received and lodged in cubicula located off to the side of the atria, similarly to the rest of the family.

G. These are the Alae, or open rooms connected to the atria. Here, imagines, or wax busts of the ancestors were kept. These were used for display as well as ceremony.

H. This is a hallway, or fauces. In a Roman home, these were hallways or passages that led from the central atrium to either the peristylium or another part of the interior of the home.

I. This is a back entrance to the home, or posticum. Oftentimes, servants or slaves would use this entrance instead of the main entrance when entering the home. Of course, the posticum has nowhere near the splendor of the main janua/vestibulum/ostium.

J. This is the culina, or kitchen! Oftentimes, the combination of being in a corner, and thus far away from both the peristylium and the compluvium, and the lack of windows (fenestrae) in the average Roman home resulted in the culina to be dark and stale. Here, women or slaves (in the wealthier families) cooked meals for the family daily.

K. Ovum is a scholar, and no scholar can go without a library (bibliotheca)! After the second Punic War, private libraries became increasingly common (public libraries had been around for a while by then), and the book collecting frenzies of Cicero, Atticus, and other scholars and intellectuals became well known. Soon enough, the practice of owning a private library became extremely common, with many people having libraries but neglecting to read a single book (liber)- simply having the library only to seem educated.

L. This is the study, also known as the tablinum. Not only did the paterfamilias complete business from home inside this room, it also held the family records and archives! Typically in a domus, the tablinum would be situated opposite to the front door, across the atrium, and have an opening to the peristylium (if not a door, at least a window). Thus, the entire house could oftentimes be seen from front to back. The tablinum also often showcased a mosaic or tiled floor, with magnificent paintings on the walls.

M. This is the dining room, or triclinium. In here, there were 3 couches (lectus), each of which could seat 3 people, arranged in a semicircular pattern elevated above and around a central table (known as a mensa) for diners to recline on as they ate. Known as the lectus imus, lectus medius, and lectus summus, each of these couches designated a special area for specific people to sit. On the lowest couch, the lectus imus, sat the host family. On the middle couch, the lectus medius, sat guests of honor. Finally, on the highest couch, the lectus summus, sat the lowest status guests. This system may seem confusing at first, however, it is quite simple why the Romans chose their seating this way! People sitting on the middle couch could easily speak with the hosts sitting on their right (as diners typically reclined on their left elbow). Additionally, they would be provided with a pristine view of the courtyard (or peristylium). Members on the highest couch would not be provided with this view.

N. This is the peristylium, or colonnaded garden! It was a courtyard with the central area open to the sky. The central courtyard had a covered portico with columns surrounding it. In the central courtyard itself, many plants could be found, as if it was a small garden in itself, including roses, rosemary, mulberry, and much more! Furthermore, small statues, fountains, or even the lararium if it was not located in the atrium could be found in the peristylium as well.

O. This is the oecus. Similarly to the triclinia, the oecus was a much larger banquet hall-ish room, with columns supporting the roof of the very large room. This was typically used for larger dinners, and was very similar in function to the triclinia. Interestingly enough, the oecus also had multiple types of styles, as mentioned by Vitruvius, the Tetrastyle, Corinthian, Aegyptian, and Cyzicene.

P. This is the garden, or hortus! Typically, the hortus was located at the back of the house, as depicted in the image. Gardens were used for both leisure and for food, with the latter being what poorer citizens of Rome typically used their gardens for. Oftentimes, footpaths or other decorative elements were also present in the hortus, along with the most popular plants of roses, cypress, rosemary, and mulberry.

These are some of the more basic rooms in the Roman domus, but of course, these aren’t all! Hopefully from reading this you were able to learn something cool, and I’ll be back with another post on some of the less common rooms soon as well!

Cheers,

Parakeet.